AND THE WAR FLOWERED

It’s wrong what they say about war. War brings death, desolation and untold suffering. But sometimes war beget flowers too. Beautiful flowers. Flowers of war.

The air is warm this evening. Everywhere around this fenced space is covered in bushes of rose flower. Their beauty accentuated by the crescent moon. I breath in, take it all in.

And suddenly, Kaleb’s voice whispers in my head: just breath, take it all in. Like always, he is somewhere lurking in my subconscious.

Today when you ask, perhaps everyone will have their own account of the war. How it begun. The genesis of it all. In truth though, nobody really knows the last spark that ignited one of the bloodiest tribal wars this country has ever witnessed. Because nothing really started the war. It just begun. Like an ejaculation whose time is due.

You know, not even the fancy fabrics we cover ourselves in or the beautiful haciendas we build for ourselves, the outstanding inventions our minds have conjured, scientific discoveries, great art we revel in…. None of these can hide one simple truth; that behind this facade we are kindred to every other beast of the wilderness. And beasts sometimes fight. No logical explanation behind it.

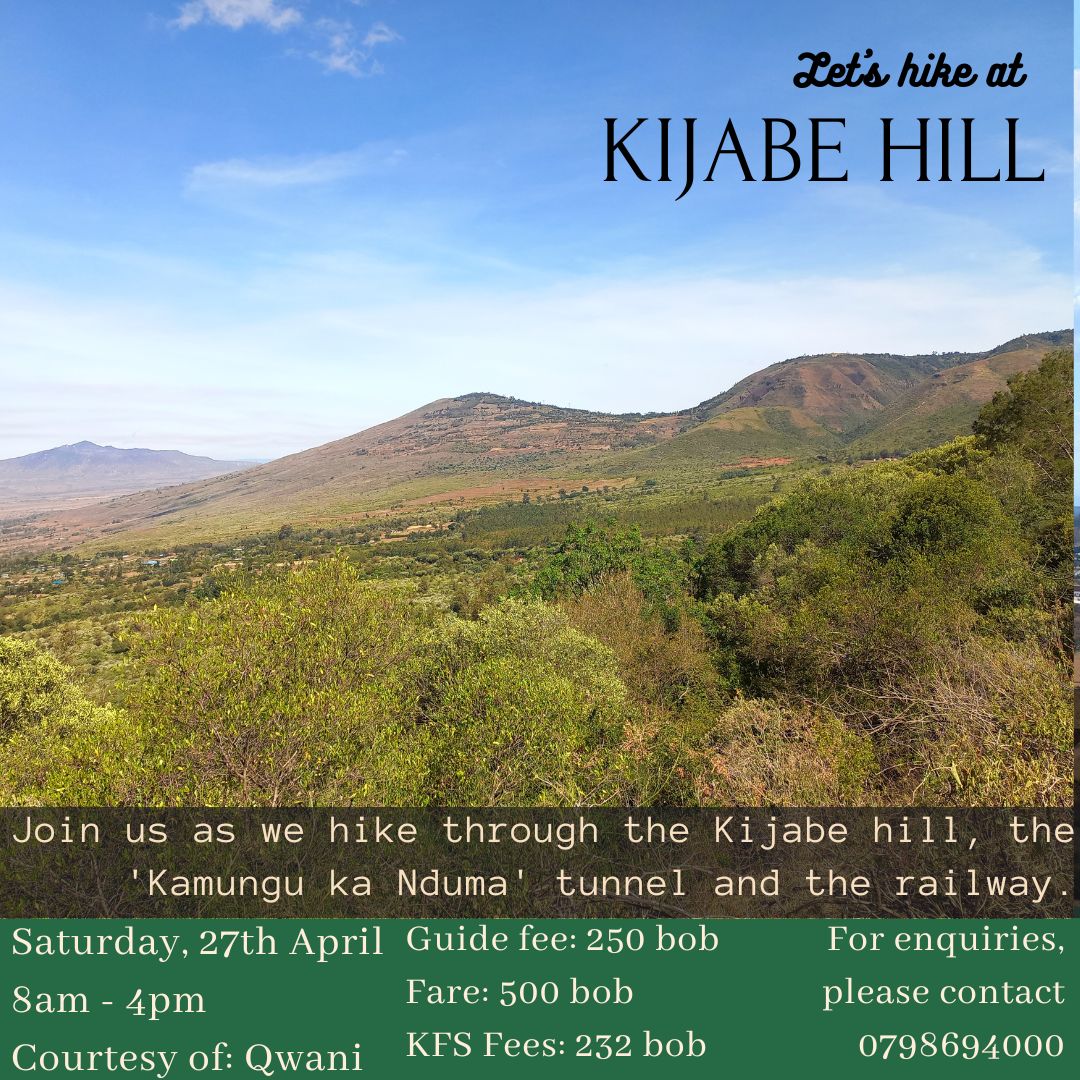

This village that lies between the thighs of two beautiful hills buried my placenta over three decades ago. It was beautiful then. The hills all green and alive, like two maned lions facing off on a duel over the control the little Hamlet below. And the rivers, fresh clear waters all flowing gracefully and to the glory of our ancestors. It’s by this river that Kaleb and I spent most of our childhood. Our fond memories still flows with the water as the river meanders along the hills towards the lake far away.

Now looking at her, the moon illuminating her two barren hills. Lifeless. Like two beasts bellowing their last death cries. The smell of death still hovers around. Everywhere you look is an evidence of man’s ability to destroy another man. Miruka village in all her glory, now just a pale shadow of her former self.

Under the same roof Kaleb and I spoke our first words. Mine was mama. His was Obedi, my name.

While I enjoyed the warmth of our mother’s thick wrapping arms and cherished the fresh milk from her bosom, Kaleb had no such pleasure. For our mother succumbed to severe haemorrhage a week after birthing him. I had been born a year before.

Baba says he smiled upon his first gulp of acrid air. Such a happy little human, oblivious of the grief he had caused by his mere existence. That he had taken a life upon his first breath did not seem to tarnish his personality one bit.

Baba never remarried. He hired a nanny to look after us when he was away, and he was forever distance in his business travels. Our maid, a young woman of Kisii ethnicity brought us up, saw us grow into lively and energetic boys. We found company in each other. Even as kids, Kaleb was quick, he was glib and generally a people’s person.

While I remained buried in books of poetry and short stories, Kaleb’s prowess in playing marble was well known far and wide. And marble game was revered by every boy in Miruka village. Sometimes we played by the river, moulding bulls using clay and ducking into the clear water clad in nothing but the love of our ancestors. Again in the water Kaleb was unrivalled swimmer. Seemingly, this lanky ever smiling boy that’s my brother was born ready made – with every skill on his fingertip.

Unbeknownst to us, our world was first changing. While we emersed ourselves in games and school and just being kids, in the real world- the adult world, tensions were fast rising, rifts forming between people who had once regarded each other as neighbours and even friends. Men had begun seeing each other in terms of us versus them. Our tribe versus their tribe.

For Kaleb and I, life was still as it was meant to be; one long party. Baba still went on his business trips only home on weekends something we had now come to accept as a norm. Sheila our nanny still made us her tasty soup, although we had noticed her reluctance to speak to us in her native language, a language she’d had devoted most of her life with us tutoring us in. She was more discreet now. As if there were eyes everywhere watching her every move.

In school both of us killed it in our own different ways. My brilliance in Sciences and mathematics was only matched with my wit in languages and literature. By the time I was in grade five, I could already recite several William Shakespeare’s sonnets much to the delight of teachers and students alike. One particular sonnet, the sonnet 18 was my every day tool for beguiling none suspecting girls I fancied;

Shall I compare thee to a summer's dayThough art more lovely and more temperate

Raugh winds do shake the darling buds may…

And my fit bird would smile coyly, quietly slipping into the trap I had set for her.

On the friday evening when I recited Christopher Marlowe’s The Passionate Shepherd to his Love in front of the whole school still remains the greatest hallmark in my life. Even Baba took time off his businesses to watch my lips, his son’s lips give life to Marlowe’s ancient words, rolling them on my tongue, tasting their touch and beauty;

Come live with me and be my love

And we will all the pleasures prove

That valleys, groves, hills and fields

Woods or steepy mountain yields

When I was through with the last line, everyone in attendance was on their feet in a standing ovation. Tears in Baba and Kaleb’s eyes said it all. They had never been more proud of me.

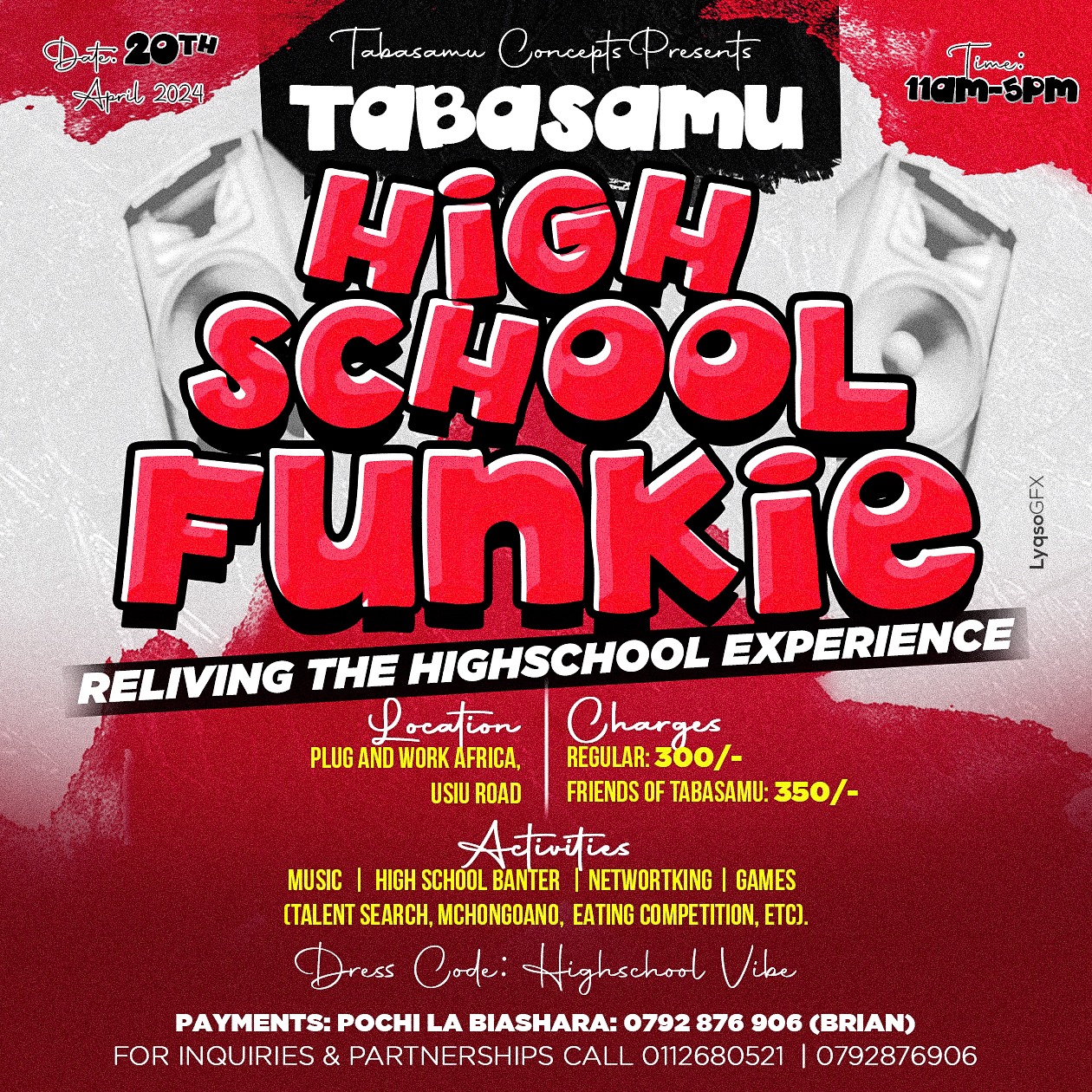

In those few serene moments humanity was one united in their love for art. Right there in that very moment no form of difference man had subjected upon himself mattered. No tribe, language, religion or race could rift them apart. It’s almost impossible to imagine these same people would come to slaughter each other on the same ground a few years later.

Kaleb took to sports like a duck takes to water. He lived football, ate football, slept football and the only thing he wanted out of life was to be like that Brazilian football maestro Ronaldo Nazário. We all knew for certain that if anyone was going to lead our country to our first world cup tournament, it would be my brother Kaleb. Except our world was fast changing and not to the better. We were only too young to notice the accusatory glances thrown on those of us who were ethnic Luo by Kisii teachers. And then there was always the whispers. Adults gethered in every place whispering in low angry tones. If Baba wasn’t always too preoccupied he would be whispering too. I bet he was just as shocked as we were when it all went down.

The planting season of the year 2001 is the day my life as I had known it changed. We were just winding up on our first class when something roared like thunder. And our desks shook a little as the sky darken with smoke. We sprung to our feet and rushed out of classrooms panic written across every kid’s face. Window glasses shattered as men armed with homemade guns and arrows stormed the school.

“Miruka is Kisii only now, Luos must find another home!” They cried death written on their faces. We were frightened. Until then none of us had ever heard gunshots.

Apparently a Kisii sugarcane plantation had been touched the previous night and Luos were accused. Now Kisiis were out for revenge and they were baying for blood. And then exchange of fire and arrows ensued. As we ran about panicking and confused, none of us had any notion that our way of life had ended.

I remember Kaleb and I crouching towards the gate. And I remember something whizzing past my ear. And then I remember nothing else because suddenly Kaleb was sprawling on the ground an arrow from the back of his head sticking out of his mouth.

The two of us, Baba and I burried Kaleb on our garden behind the house that night. Sheila, the nunny had left a day before to I don’t know where. I would never forget the grief on Baba’s face that day. The pain in his eyes, the fear. Then I saw Baba do what I had never known him capable of doing. He cried. Baba wept like child. That same night Baba and I traveled to South Africa. Three decades later, only one of us made it back alive.

It’s getting dark. The clouds are slowly covering the moon. Soon it will be pitch dark, perhaps it will even rain. I cast one last long look at the fresh mound of Baba’s grave. I lay bunch of flowers where his head is suppose to be.

“You’ve had a long life old man, rest easy”, I mumble to myself.

Nearby is Kaleb’s grave. Covered in lovely flowers, as beautiful and as vibrant as he himself had been in this life. These flowers of war…